Accidents of Material and Chance: A Conversation with Laura Waddington

By Pamela Cohn

We finished this virtual interview on the day in March 2020 that a State of Emergency was declared in Portugal and that Lisbon, where I was living, went into lockdown. The graphic novel that we discuss below and that I was putting the final touches to, had to be put aside for more than two years for reasons related to the pandemic. Only later could I have all my drawings photographed and replace the homemade scans that accompany the print copy of this article, in the digital mockup. At the time, I decided to rewrite the book’s introductory texts and end notes and to change the title to ‘M’s Story’ (insetad of ‘Are you a river? M’s Story’ as mentioned below). The original conclusion referred to in my first answer, is also no longer part of the upcoming book. (LW)

*

London-born filmmaker Laura Waddington shot her films CARGO (2001) and Border (2004) with a handheld Sony TRV900 mini-DV cam. For Border, she shot in the fields around the Sangatte Red Cross camp in France, staying close to the Afghan and Iraqi refugees as they attempted to get to the UK by hiding on the trucks that were moving through the channel tunnel at night. In a series of reflective writings about her oftentimes harrowing adventures in filmmaking called Scattered Truth. she asks, “Is it still possible to draw the spectator into a space where they can look at an image for the first time without the uncanny impression they have already seen it and all the images yet to come?” This was a profoundly prescient query considering that only four years after her time in Sangatte, Laura would meet an Iraqi refugee in Amman, Jordan she calls “M”. As Laura was readying herself to leave the table where she’d shared an afternoon of tea and conversation with M and his wife, he started to share the account of his kidnapping, imprisonment, and torture when he was a teenage soldier completing his military service under the dictatorship of Saddam Hussein. To protect his identity, Laura kept the lens cap on her camera while recording M’s narrative in its entirety.

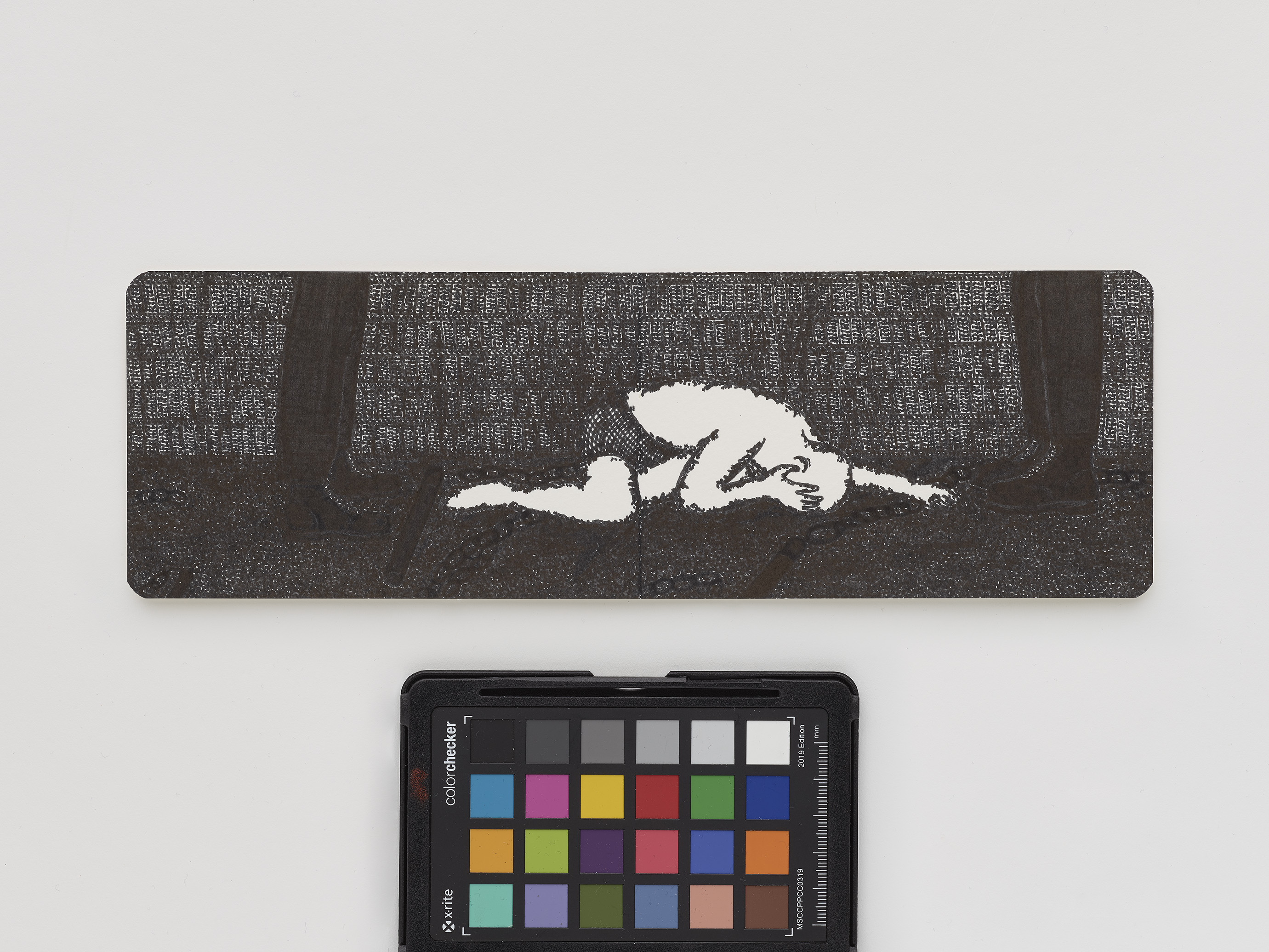

Although she endeavoured to, Laura never found a way to portray M’s story in a film. She says: “It wasn’t only due to practical constraints and my unease at depicting torture. My old mini DV cameras, now phased out of production, had allowed each story and the way it should be filmed to emerge gradually, in part out of technical accidents and chance.” Since that was not possible this time, she taught herself to draw and created a graphic novel instead. Are you a river? – M’s Story (forthcoming) consists of M’s verbatim account and the hand-drawn frames that took hold in her imagination. Here, Laura talks about the circumstances that led her to draw M’s tale and the process of discovering the power and “improvised nature of the pen, with its lack of claim to document accurately.”

PCWhat stands out to me about the way you write about your artistic journey is how profoundly hooked into your dream state you are and how signals from your subconscious provide some kind of foreknowledge of things to come. Many years ago, you presciently wrote about the possibility of encountering a story that you had to tell but it would be one ultimately impossible to film.

LW Part of my work unfolds in a very logical and researched way but it is dreams and instinct that propel my work forward and often lead me to undertake a project. In the conclusion of the graphic novel, I write about the effect of spending years working on the subject of torture. I began to get sick and I believe it was in part a reaction to the horrific images that I so intensively researched. Amongst other things I developed electro-magnetic hypersensitivity. This has opened up a whole other world because there is a lot of denial around the condition, and both the symptoms and the sufferers are invisible. What was interesting was that at that time, my levels of prescience increased. I regularly saw things before they happened in precise detail and this became un-livable. So now, I am trying to dial the prescience back. For the first time in my life, I am trying to close my ears and eyes and be less sensitive to the world. The experience has brought me face to face with the question of what to do when you can’t talk about a subject because society says it doesn’t exist.

PC The challenge of how to convey M’s story alongside these drawings without the reader crashing into a state of suspended disbelief must have been significant.

LW Yes. The impetus for how I depicted it came in part out of frustration when I returned from Jordan and told people what I’d heard there – which in many ways contradicted the general discourse about Iraq in liberal and left wing European circles at the time. A number of people immediately retorted with reasons why I must be wrong or had been lied to, leaving no room for discussion. It felt like a glimpse into where we were headed: into today’s world of social media bubbles and the increasing difficulty many people have dealing with information that doesn’t neatly fit into and prop up their worldview. After a few weeks, I gave up talking about what I’d seen and heard. One night at a party in Brussels, I encountered an Iraqi woman. She told me how angry and defensive people would become when she tried to explain to them what life had really been like under Saddam Hussein’s regime. She’d resigned herself to keeping silent. She smiled wistfully and said: “But we know it, and you know it, and that’s something.”

In that context and because I didn’t know how to draw, the only possible way to approach it was without any preconceptions. Each time that I sat down at the table with my pen, I would completely empty out my mind and strip myself down mentally. So the drawings were made in a kind of haze. If I’d let my intellect enter into the process, I would likely have become completely blocked. The very precise and inscribed nature of the sketches was an instinctual response to those who had not believed me or believed M’s account. All of my distress and outrage at people attempting to deny his story went into the little details of those drawings. I would like to emphasize that the drawings are completely fictional. Every word of the text is as M told it to me but the drawings could only ever have been imagined.

PC You drew distilled black and white representations of one man’s memory of a brutal experience. Can you speak to some of the narrative imperatives for the illustrations that would offset M’s words?

LW Black and white creates a level of abstraction and I think a distance that can lull readers into thinking that things won’t hit them as hard. The choice to work exclusively with a black pen came from my need to keep things as simple as possible due to my lack of experience. But as I drew, I began to conceive of the distillation of black and white as a way of leading the reader into the space, and then exposing the horror in a manner that was perhaps unexpected and in a certain sense bearable. How to show the horror? How to avoid being merely anecdotal when all I did was listen to M?

PC The book feels much more definitive in its stance on the truth than your documentary work in video. How interesting that hand-drawn frames feel so much more rigorously documented even though they’re imagined.

LW I couldn’t have made this work on video. The very material of video, and even more so High-definition video, would have added a level of violence that would have made it unwatchable. It is very difficult in the act of filming a subject like this for the camera to not become violent and invasive towards the subject and the spectator. Because I was not filming, and confined to the space of the page, I had a much larger spectrum of possibility to completely enter into the horror of the story. I had the impression that my lack of experience and the relatively clumsy nature of my drawings could provide a level of protection, a kind of buffer for the reader, which in turn allowed me to go much deeper than in film. When you deal with a subject like this, you are constantly aware that the act of portraying torture is obscene, every drawing was a battle with that. I came to conceive of the slowness and difficulty of the act of drawing, the duration involved in making a graphic novel, as a potential antidote to that obscenity. Though I am sure some people will disagree.

PC In your process of drawing the book, did you discover or re-discover further limitations about working in film and video and the, oftentimes, skewed power dynamics of recording images? Did that also become a preoccupation for you as the illustrator of someone else’s true story as you began to learn more about the possibilities of the graphic novel form?

LW I had only read one graphic novel when I started drawing M’s story so I discovered the medium as I progressed and became full of admiration for graphic novelists – both for the freedom and adventurousness of their work, as well as the amount of time and solitude it demands. There are people who work on one book for seven or eight years. That’s a really brave thing to do in this tyranny of the “now” in which we live. The graphic novels that I discovered while drawing really kept me going because many people around me could not understand what I was doing, why I would take the risk of walking away from film to do something that I had no idea how to do. They thought it was a sign of profound failure that I was taking so many years to do it. But I began to see it as a free space and a space where an image can be made and looked at in an un-tampered way.

PC Do you think you’ll find those kinds of free spaces with a camera again?

LW I began this project as a filmmaker so when I went to Jordan in 2006 it was with the idea of researching a possible film. When I returned to Europe several months later and was confronted with the fact that certain people didn’t believe M’s story and that I couldn’t find an effective way to film it, I went through a period of metaphorically banging my head against a wall. Layers and layers fell away until I understood that the telling of the truth, as I perceived it, was far more important to me than my identity as a filmmaker – or my identity, full stop. Today, I do not know what I am except that I am someone who wants to record and chronicle things. To tell or chronicle things that I believe in has become more important to me than the medium in which I do it.

And I think that whatever medium I used to tell M’s story, I would never have been satisfied with the outcome. It was necessarily going to fail. And there would always have been the limit of my being an outsider to his story. The fact that the drawing took so much time, concentration and attention, and that it demanded I take on a whole new medium starting from scratch, was perhaps the only approach that could leave me with some peace of mind. When I had initially failed to find a way to tell M’s tale in a film, it became clear to me that if I didn’t find a way to tell it, I wasn’t going to be able to create again. It was a watershed moment that is very difficult to explain. One person told me a story and everything changed in my life because of it. I have no explanation for that. It’s a powerful and terrifying story but I’ve heard a lot of powerful stories. I’d set out on a path to make films and I believed I’d always make films. I had been very lucky with how things had unfolded up until then, all my previous films had followed on from each other naturally. But in this moment of reckoning around M’s story, everything changed.

PC What is the origin of the title “Are you a river?”

LW Badr Shakir al-Sayyab was a famous Iraqi poet who wrote, amongst other things, the beautiful poem “The Rain Song”. The title of the graphic novel comes from some lines of his poem “Death and the River”:

“…river of mine, forlorn as the rain.

I want to run in the dark

gripping my fists tight

…Are you a river or a forest of tears?”

My drawings recount M’s experience but I recorded months of Iraqi testimonies and conversations and I really did have the impression of “a river or a forest of tears” because the Iraqis have endured decade upon decade of pain and darkness. But the counterbalance is the resistance of culture and the intellect in Iraq, particularly the powerful role that poetry plays there and throughout the Arab world. I wanted a sign of that to be present. In my diary from that time, I wrote about the way in which the Iraqis fought to keep culture alive under the embargo, the unending resilience of books and ideas and their will to preserve them at all cost.

I don’t think you can push the horrors and violence of the world onto people without counter-balancing it with humanity and beauty. At the moment, we are seeing what goes wrong when you push nightmare after nightmare onto people in news feeds and on social media without proper framing or context. It fills people with fear and anger and they retreat into tribal allegiances. As humans, we are wired to tolerate only so much. This was, of course, a worry with this project. Could my way of rendering the story create the necessary distance or would I be adding to all the pain and violence? When I am trying not to lose hope in the current state of the world, every time I hear just one thinking person’s voice, it’s always his or her rigour of thought and application that gives me the courage to go on. That individual rigour and devotion of just one ordinary person is so important because if everything around us becomes too flimsy, we will all collapse.

Source

Cohn, Pamela. “Accidents of Material and Chance: A Conversation with Laura Waddington.” Non-Fiction (Journal from the Open City Documentary Festival, London), no. 1 (special issue: Power), Spring 2020: pp. 12–17.

Back to top