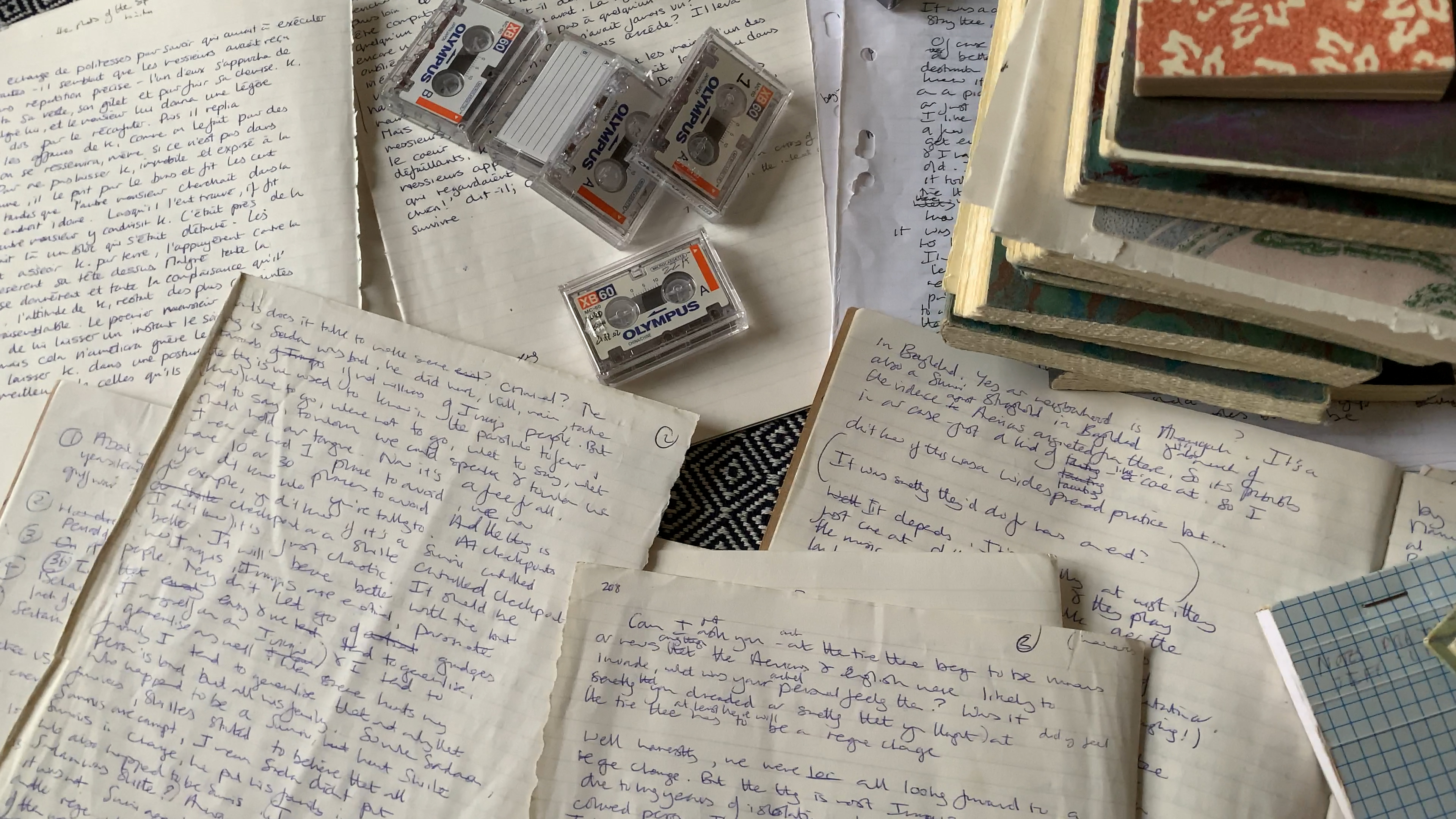

Excerpt One from the Iraqi Suitcase

By Laura Waddington

Early pages before my departure for Jordan:

Still in Venice. I am lying on the bed in my hotel room, listening to Fairuz, the curtains swaying back and forth in the breeze. It’s cold despite it being summer, the window open, the sound of water lapping in the canal below. On the television, I fall upon an interview with Erri de Luca, the Neapolitan writer, who worked as a labourer on building sites and taught himself to read ancient languages before starting to write. Books of beautiful fragments, as if he is wandering through time with a torch light, gathering up all the unnoticed words and encounters of history that inspire him. “There are circumstances which forbid us to remain with our hands in our pockets,” he tells the interviewer of his decision to travel to Belgrade during the NATO bombings because he preferred to be a “target.” He used to drive trucks in humanitarian aid convoys into Bosnia during the war in ex-Yugoslavia.

I think of the generous and defiant priest Don Vitaliano who welcomed me and my friend Angela in the hills around Avellino a few years ago, on our way to film the packed boats of migrants arriving on the island of Lampedusa. He had, I discovered during our days with him, been a human shield in Baghdad, spent time with the Zapatistas in Chiapas, marched against the G8 summit in Genoa. A rebel, full of gentle humour and resolve, whose actions unsettled people high up in the Vatican. “Obedience is no longer a virtue,” he said.

One afternoon, he drove us to a small city in the hills of Campania to meet his friends, members of a radical volunteer association. One of them, a young metal mechanic who volunteered as an ambulance worker in his nights and days off, described to me, still shaken, how he had been called out to a petrol station one morning in the midst of a terrible storm. There a distraught lorry driver from Rome had led him to a long orange truck, inside one section of which was a diplomatic car that he was transporting from the Italian embassy in Sofia.

Lying on the ground, in front of the truck, in the torrential rain, were the soaked bodies of nine young Kurdish men, some with their eyeballs out of their sockets, others barely alive. Walking back from the rest stop, the lorry driver had heard banging coming from his vehicle and had rushed to unbolt its door, and five corpses had fallen onto him, followed by the bodies of four more young men, vaguely conscious, gasping for breath, one of them clutching a screwdriver.

One of the survivors would die a few days later in intensive care. But the ambulance worker, Don Vitaliano, and the members of the volunteer association, would grow very close to the remaining three, going back and forth to the hospital each day to bring them bottles of water and to provide support. And the youngest recounted to them what had happened:

He had set out alone from a town in Iraqi Kurdistan. He was fifteen years old (although he had told the Italian police that he was seventeen). He wanted to get to England and to become an ambulance driver. He had encountered the others en route and they had walked together over the Turkish mountains, and then on to Greece; about twenty days on foot. They all came from the same town as him, save one, and their families had sold everything they had for them to make their journeys, each one paying four thousand five hundred dollars to smugglers. The smugglers had promised them that it was very easy to get to England.

In Greece, they had spent several months in the port of Igoumenitsa trying to hide inside one of the trucks bound for Italy. When the long orange truck had appeared, the smuggler had warned them that it was too dangerous to hide inside: it was a diplomatic truck, he said, its two trailers tightly sealed, and they would be concealed deep inside. But after months of waiting in the port, they were growing impatient and decided to go against his advice (or was that just a story that the smugglers had instructed them to tell the authorities if they were discovered, wondered the Don Vitaliano and the volunteers, and was it actually the smugglers who had put them inside the truck?). If you feel ill and can’t breathe, the smuggler instructed them, push on the door and shout.

They found themselves squeezed into a dark, low, airless compartment, crouched around the diplomatic car, as the truck made its way across the sea. A few hours into the night crossing, they started to became ill but they assumed that it was just sea sickness. One of them lost consciousness then. They banged on the door for several hours to raise the alarm but no one heard.

In the morning, when the ferry reached land and the sun started to shine down on the truck, it quickly became hotter inside the small compartment and more difficult to breathe. It was then, in the hours before the storm broke, that they understood that they were dying from lack of oxygen. Gasping for breath, they discussed what to do. One of them had the idea that if they turned on the air conditioning in the diplomatic car, it would provide them with air to breathe. They turned on the car’s ignition and got the air conditioning running. Almost immediately, they understood their fatal mistake. By then there was so little oxygen left in the compartment, they had only accelerated their deaths.

As the truck moved along the motorway, the remaining young men were slipping out of consciousness. The youngest had been banging on the door and walls for hours now. Some of them decided to destroy the door of the truck by ramming the car into it but when they turned the car’s engine back on and put it into gear, it wouldn’t move. So, they tried to prise open the lorry’s door with some screw drivers and a spanner that they had found in the car, and to enlarge a small hole, through which a little bit of light was penetrating. But nothing worked, as if they were imprisoned inside a hot fridge. More of them were dying now and the youngest lost consciousness.

When the driver put on his brakes on his arrival at the service station in Avellino, he, the youngest one, came around with a jolt and found the force to start beating on the door again.

Once released from hospital, he and his two fellow survivors stayed for a while in the small Campanian city with the volunteers. He did a few rounds with the ambulance crew and then someone offered him a job. He considered staying and making a life there but decided to pursue his original goal to get to England with his companions. So some people gathered a bit of money to help them to continue with their journeys, and the volunteers and Don Vitaliano bought them train tickets to Rome, where they had contact with smugglers. In Rome they hid inside a truck headed to France, and then they were smuggled into Britain.

What became of the five young men who had perished inside the truck? When the Italian police found their corpses lying on the ground in the storm, they had false documents on them, so the police had registered them as “persons of unknown identity.” The Italian authorities were therefore categorical that they should be buried in anonymous graves in a makeshift cemetery, like all those who die on their clandestine journeys through the country. But the volunteers, Don Vitaliano, and some of the local citizens were determined that the young men should be named and returned to their families and homeland, to be mourned properly and buried with dignity.

They now discovered that there existed a smuggling route operating in the reverse direction to return bodies to Iraq. It had grown up because both Iraq and Iran refuse to issue permits to receive corpses back, while the Syrian state had never officially given its accord for a body to be flown into Damascus and driven on to Kurdistan. So, a funeral home in Brindisi had been transporting corpses back via Damascus, using a combination of trickery and bribes, in conjunction with smugglers. But the funeral director said there was too much focus on this case for them to get involved.

The only possibility was for the volunteers, Don Vitaliano, and the local communist politicians of Campania who now joined them in their quest, to persuade the Italian state to release the bodies and the Syrian state to officially accept them, with legal passports issued for them to be driven onto Kurdistan, even if this had never happened before.

So, they entered into battle against truculent bureaucracy. While the inhabitants of the small city and its surroundings busied themselves raising money “to get the boys home,” the volunteers and Don Vitaliano managed to find and make contact with the families of the deceased young men in Iraqi Kurdistan. Learning that they had relatives living in Munich and Oslo, they arranged for the relations to travel to Italy for a week to officially identify the corpses. But the Italian state still wasn’t satisfied. It wanted an official request for the return of the bodies to come from Iraq. So members of the families in Kurdistan travelled to Baghdad to obtain official stamps from Saddam Hussein’s regime, to prove that the young men now lying in the morgue of the Italian hospital for weeks were their kin. Once these stamps were delivered to the police station in Avellino, the official process to release the bodies could finally begin.

The region of Campania and its people would eventually pay thirty-five thousand euros to repatriate the bodies, and with money and dogged persistence, they persuaded the Syrian authorities to grant authorisation, for the first time ever, for the corpses to land in Damascus and to be driven on through Kurdistan.

When the truck containing the young men’s remains arrived in Kalar, the city in Iraqi Kurdistan where one of them was born, it was greeted by tens of thousands of people lining the streets waving Italian flags and a feast was laid on in honour of the Italian government. Although, were it not for Campania and its determined citizens, rather than the Italian state, Don Vitaliano and the volunteers laughed, the young men would be buried in Italian ground: “they didn’t want to release the bodies!”

“I think the civility of a people depends on such things, the way it treats people,” said the director of the volunteer association a few times as he recounted the story to me.

Shortly after our stay in Avellino, Don Vitaliano was expelled from his parish, and the old women of Sant’Angelo a Scala chained themselves to the church doors in protest. When that didn’t work, the inhabitants walled up the entrance of the church to demand his return. But nothing would persuade the Vatican to return their priest to them.

Source

Waddington, Laura. Excerpt One from the The Iraqi Suitcase. (Upcoming publication).

Back to top